Cancer cells team up to scavenge for nutrients, reveals new research.

The discovery that cancer cells cooperate to survive could lead to more effective treatments for the deadly disease, say American scientists.

The process was previously overlooked by scientists, according to the study published in the journal Nature.

Senior author Professor Carlos Carmona-Fontaine, of New York University, said: “We identified cooperative interactions among cancer cells that allow them to proliferate.

“Thinking about the mechanisms that tumor cells exploit can inform future therapies.”

Scientists have long known that cancer cells compete with one another for nutrients and other resources.

A tumor becomes more and more aggressive as it becomes dominated by the strongest cancer cells.

However, scientists also know that living organisms cooperate, particularly in harsh conditions. For example, penguins form tight huddles to conserve heat during the extreme cold of winter, with their huddles growing in size as temperatures drop.

The researchers explained that, similarly, microorganisms such as yeast work together to find nutrients, but only when facing starvation.

Cancer cells also need nutrients to thrive and replicate into life-threatening tumors, but they live in environments where nutrients are scarce.

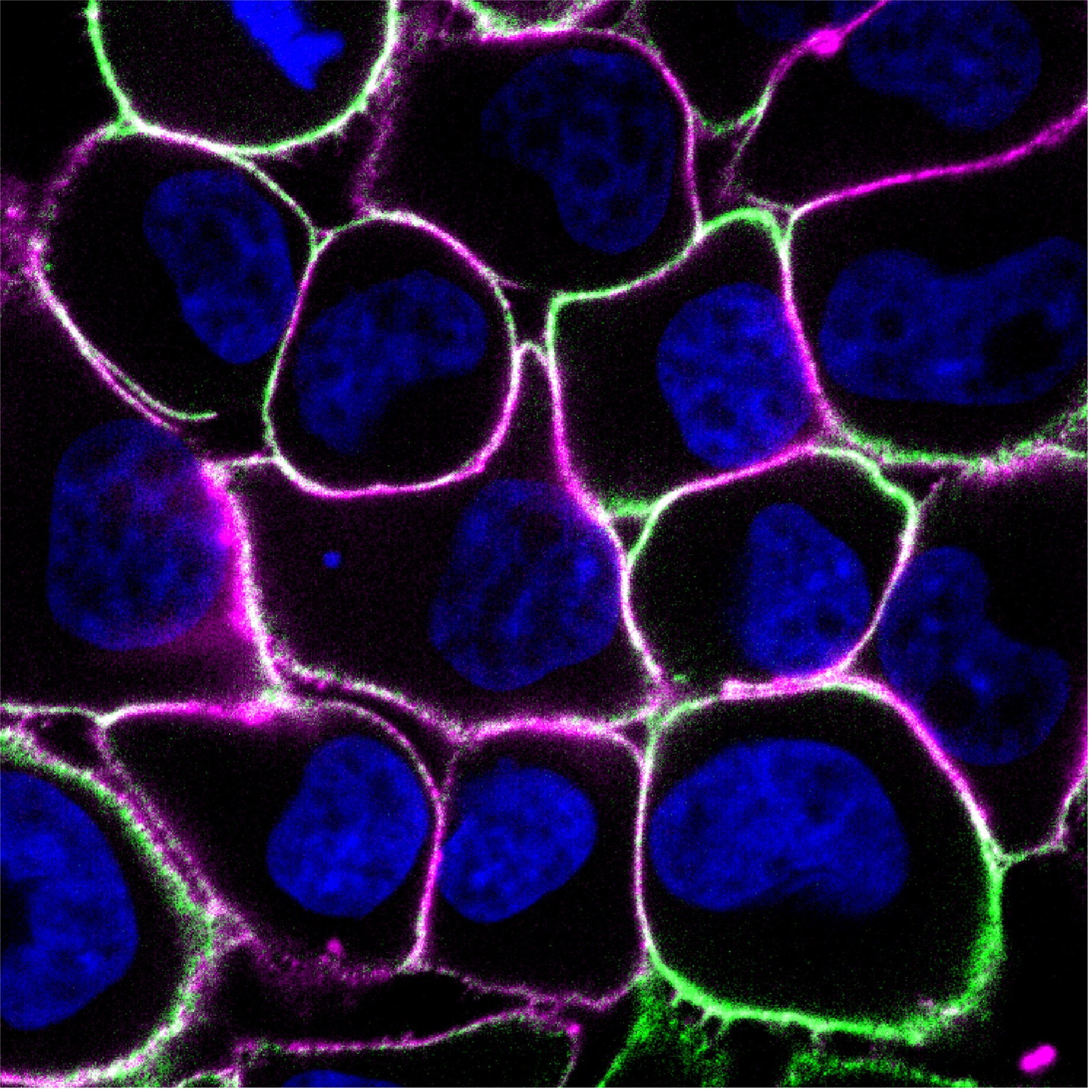

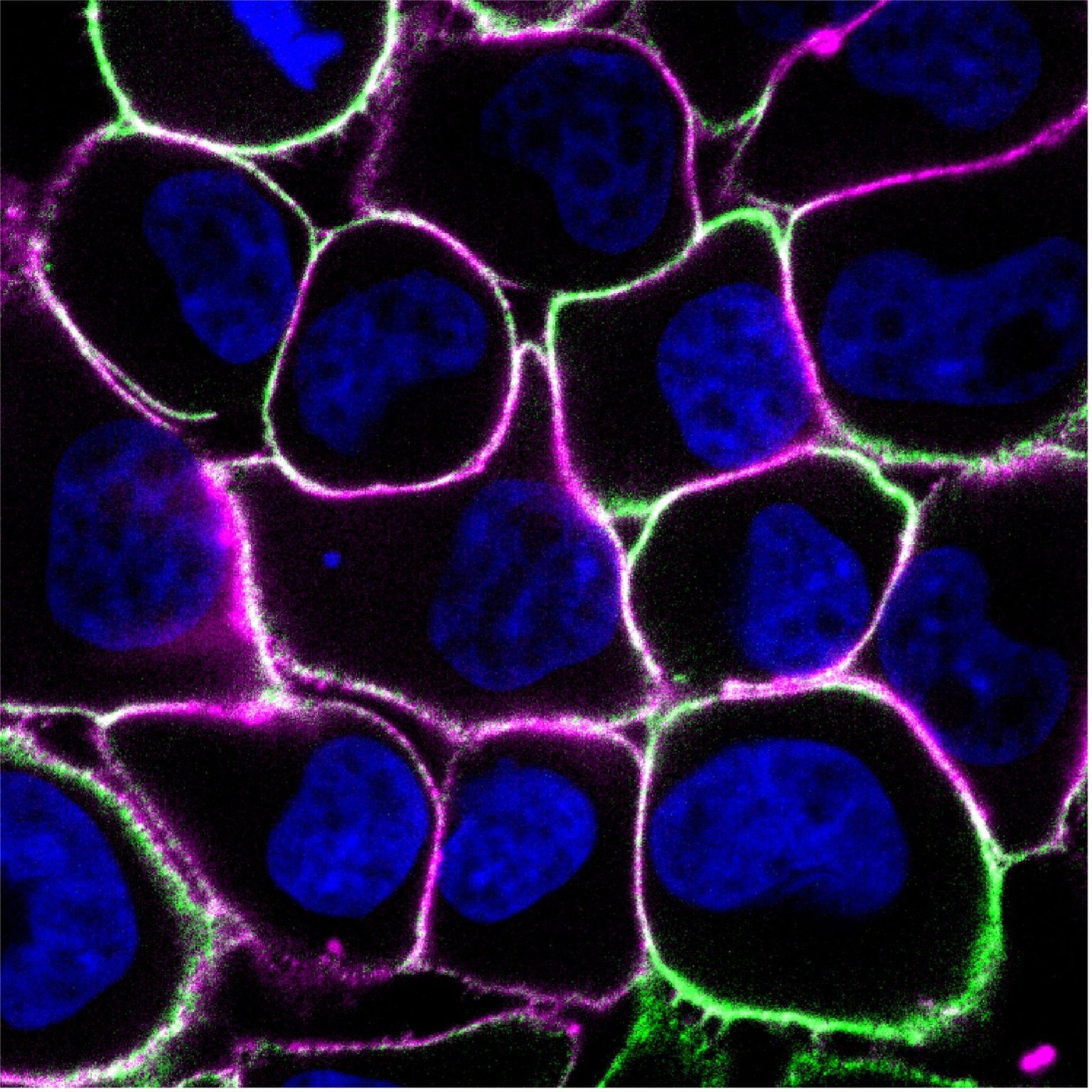

To determine whether cancer cells cooperate, the research team tracked the growth of cells from different types of tumors.

Using a robotic microscope and image analysis software they developed, they quickly counted millions of cells under hundreds of conditions over time.

The approach allowed them to examine tumor cultures at a range of densities – from sparsely populated dishes to those crowded with cancer cells – and with different levels of nutrients in the environment.

It was already known that cells uptake amino acids in a competitive manner.

But when the cancer cells studied were starved of amino acids, such as glutamine, all of the cell types tested showed a “strong need” to work together to acquire the available nutrients.

Prof Carmona-Fontaine said: “Surprisingly, we observed that limiting amino acids benefited larger cell populations, but not sparse ones, suggesting that this is a cooperative process that dep on population density.

“It became really clear that there was true cooperation among tumor cells.”

Additional experiments with skin, breast, and lung cancer cells showed that a key source of nutrients for cancer cells comes from oligopeptides – pieces of proteins made up of small chains of amino acids – found outside the cell.

Prof Carmona-Fontaine said: “Where this process becomes cooperative is that instead of grabbing these peptides and ingesting them internally, we found that tumor cells secrete a specialized enzyme that digests these peptides into free amino acids.

“Because this process happens outside the cells, the result is a shared pool of amino acids that becomes a common good.”

He says determining the enzyme secreted by cancer cells, called CNDP2, was an important discovery.

The research team identified the enzyme by testing different drugs to see if they kept tumor cells from digesting oligopeptides into free amino acids.

When the drug bestatin was applied to cancer cells, inhibiting the function of CNDP2, cells were unable to feed on oligopeptides and were driven to extinction.

Now that the researchers knew CNDP2 was a factor behind the cooperative process feeding cancer cells, they could test what happens when the enzyme is missing.

The team used the genetic editing technology CRISPR to delete – or “knock out” – the Cndp2 gene, which produces the CNDP2 enzyme, in tumor cells.

They then looked at how the cells formed tumors in mice and compared their growth to tumors formed by identical cells still carrying the Cndp2 gene.

The growth of the knockout tumors was “significantly” reduced – a difference that was even more pronounced when the deletion of Cndp2 was combined with restricting the tumor’s access to amino acids using diets low in the nutrients.

The researchers were also able to reduce the growth of tumors with normal CNDP2 by combining the diets with bestatin, a combination which they say could help treat cancer patients.

Prof Carmona-Fontaine said: “Because we’ve removed their ability to secrete the enzyme and to use the oligopeptides in their environment, cells without CNDP2 can no longer cooperate, which prevents tumor growth.

“Competition is still critical for tumor evolution and cancer progression, but our study suggests that cooperative interactions within tumors are also important.”

The research team hopes that their findings will help develop cancer treatments that target cooperation among cancer cells.

Prof Carmona-Fontaine described it as “a conceptual contribution that will have an impact in the clinic.”

He said the drug bestatin has been safely used in humans for decades as an add-on to chemotherapy, particularly in Japan, but has limited effectiveness on its own.

Prof Carmona-Fontaine added: “We hope that a clearer understanding of this mechanism can help us make drugs more targeted and more effective.”